As your child nears the end of their early childhood years and edges toward elementary, you may begin hearing the term cosmic education . Ever wonder what Montessori folks are referring to when they say this? The short answer is that cosmic education is the term Maria Montessori gave to the elementary cultural curriculum (and by cultural, we mean history, science, and geography).

As you may have guessed, to truly understand cosmic education, it takes much more than a short answer. Read on to learn more!

Hallmark Traits of the Second Plane

Before we explain what cosmic education is, it will help if we explain why it was developed in the first place. As you know, Montessori education relies heavily on our knowledge of the developmental characteristics of children. As children grow and change, so should our approaches in how we serve their educational needs. Montessori organizes the stages of development into four planes, and children ages 6-12 fall within the second plane of development. Some of the most notable characteristics of children this age include:

Montessori education takes these unique characteristics into account with the way we approach our work with children in both lower and upper elementary. We allow for more social work experiences, we give plentiful opportunities for cultural learning, and even the lessons and materials were created to appeal to the needs of school-aged children.

A Deeper Definition

When we think about cosmic education, we think about our aims to give children a bigger picture of the world, their place in it, and the interconnectedness of everything. It is during this time they begin seeking answers to questions related to these topics, and their desire to learn as much about the world as possible is satisfied by the large amount of information available in their classroom environments.

Each year during the elementary years begins with a study of the beginnings of the universe. From here, and throughout the year, the study trickles outward. Children may learn about our solar system, basic chemistry, or how science experiments are conducted.

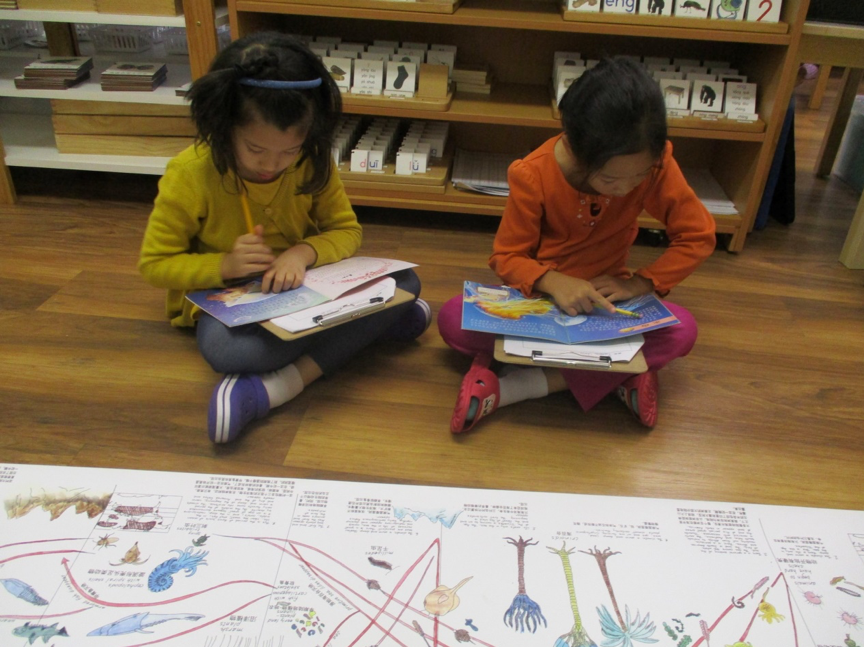

They learn about the evolution of life on earth, as well as in-depth unit studies in botany and zoology. There are opportunities for research (independent and alongside peers), presentations, and exploration.

The children learn about our ancient human ancestors, the civilizations of centuries past, and the origins of writing and mathematics. The latter are perfectly timed, considering elementary children are in the process of discovering reading, writing, and math for themselves.

Impactful Lessons and Materials

Have you heard of the Montessori Great Lessons? These five impressionistic lessons are considered the springboard into cosmic education. They are theatrical and make quite an impact on children. They are presented in a storytelling fashion, which appeals to children’s imagination, yet they are rooted in facts, which appeals to their desire to learn the truth.

Each of these five lessons is given repeatedly throughout a child’s years in elementary, and each time they receive a lesson they will glean something new from it, and the follow-up studies may be different as well.The first great lesson is dramatic and exciting. Students enter a darkened room with soft music playing. After they are seated, the guide begins telling the story of when everything was darker and colder than they can imagine, and how a great flaring forth was the beginning of our universe. There are moments in the lesson when they are shown grains of sand in comparison to the number of stars, they learn about the attraction and repelling of particles, how weight and density affects matter, and what the three states of matter are on earth.

Following this storytelling lesson, the class will launch into a different, related unit of study each year, giving children the ability to see things from a different perspective.

Before the second great lesson, students are able to interact with a number of materials that put the vastness of time in perspective. The Clock of Eons reimagines Earth’s history and major periods of time on a 12-hour clock. The Long Black Strip illustrates how much time passed with an actual long black strip of fabric, before reaching a tiny section of white at the end, signifying human’s history on the planet.Children love learning about animals, so this particular work is always approached with great enthusiasm. The main material used is called the Timeline of Life, and it colorfully and beautifully illustrates the evolution of life on our planet from the early Paleozoic Era through today. Being able to see how life has changed over time, and even the ways in which it has remained the same, always makes an impact on children.

This work naturally lends itself to in-depth studies of both plants and animals, with various methods of classification.Touched upon in lower elementary, but often emphasized in upper elementary, there is a timeline to support this study as well. We are all fascinated to learn about our ancestors, and it gives children a sense of gratitude for those that have come before us and for all the great work that has been done throughout history.

Not only do children have an opportunity to study early hominids, but as mentioned earlier they take a look at the early great civilizations and how they changed over time.Math is a subject that grows in sequential building blocks, and so it was with the discoveries of various mathematical concepts. Over time, humans discovered more complex and abstract ways of expressing the numerical world. Just as with learning about the beginnings of writing, children are always excited to learn about how math has evolved throughout time and in various cultures.

Now that you have a basic understanding of cosmic education, we would love to hear what you think. Curious to learn more? The best way is to see it for yourself. Call us today to schedule a visit.

Warm regards,

Candice Lin, Director

We invite you to visit our school, meet the teachers, and observe the children in their classrooms. We encourage you to ask questions and learn about the opportunities available at all levels of our programs.

LakeCreek Montessori International School

10127 Lake Creek Parkway, Austin, Texas, 78729

Powered by Nido Marketing