Stages of Development Series: Childhood

Discover the key traits of childhood development (ages 6-12) and how Montessori education nurtures reasoning, independence, and social growth in this crucial stage.

Understanding human development at each stage is crucial to fostering optimal growth. This belief forms the foundation of Montessori education, which is deeply rooted in the developmental needs of children.

This post is the second in a series that explores the four stages of human development: birth through age six, ages six to twelve, ages twelve to eighteen, and ages eighteen to twenty-four. Each of these stages, or planes of development, comes with unique needs and capacities, and understanding them allows us to better support children in their educational journey.

Childhood (Age Six to Twelve)

Unlike the dramatic changes seen in infancy and adolescence, the second plane of development (ages six to twelve) is often viewed as a period of relative stability. This phase serves as a critical time for children to build upon their early experiences while preparing for the transitions that will come in adolescence. Despite its importance, this period is sometimes overlooked in society, but it is essential for the development of social, intellectual, and emotional skills that will serve as a foundation for later life.

Key Characteristics of Elementary Children

At the core of this stage are several observable characteristics.

Physical Sturdiness and Stability

Children in this stage experience a steady period of physical growth. They lose their primary teeth and gain adult teeth. Their skin loses its baby softness. Their hair even gets coarser and darker. Their body becomes leaner and stronger, with the soft, rounded contours of early childhood giving way to a more defined physical form. Despite these changes, growth slows down compared to the rapid pace of the first plane. This time also brings greater stability in health and coordination.

Reasoning and Abstraction

While children in the first plane absorb information effortlessly and even unconsciously, the second plane is marked by a growing capacity for reason and abstraction. No longer content with simply absorbing facts, children seek to understand the underlying causes of things. They begin to ask “why” questions and develop the ability to think logically and critically about the world around them. Their imagination flourishes and they love being able to transcend time and space, mentally traveling through history or exploring possible futures.

Conquest of Independence

This is a time when children transition from sensorimotor learning to becoming intellectual explorers. The intellectual independence they gain during this phase fuels their studies of mathematics, history, geography, art, and music. Montessori classrooms provide opportunities for children to explore these subjects with the motto: “Don’t tell me. I’ll figure it out myself.” Their journey toward independence extends beyond the academic to include a growing capacity for social reasoning and moral judgment.

The Herd Instinct and Socialization

One of the defining features of children in the second plane is their social nature. Children at this age exhibit a strong "herd instinct"—the need to belong to a group and collaborate with peers. They begin forming micro-societies and creating their own rules, roles, and expectations. These experiences allow them to practice social interactions and develop their conscience. It’s worth noting that as adult-directed activities (e.g. afterschool sports and classes) increase, children have fewer opportunities to work out social dynamics independently.

Moral Development and a Sense of Fairness

As elementary-age children seek independence, they also begin to develop a sense of morality. Children at this stage are sensitive to fairness and justice, and are likely to voice concerns when they perceive inconsistencies. This is when we frequently hear, “It’s not fair!” This stage is about the exploration of right and wrong and the ability to question rules and authority. The drama that unfolds in the classroom is often part of this process, as children navigate the complexities of social rules and develop their moral code.

A Fascination with the Extraordinary

Second plane children are drawn to the extraordinary, whether in the form of superheroes, mythical creatures, or fascinating civilizations. Their imagination is sparked by the idea of powers beyond the ordinary, and they are eager to explore cultures and histories that seem larger than life. This fascination with the exceptional provides them an avenue for exploring concepts of heroism, strength, and the human condition.

A Supportive, Community-Based Learning Environment

In a Montessori classroom, children are encouraged to work both independently and in groups. As such, the prepared environment of the second plane is designed to foster collaboration while allowing space for individual exploration. Group activities allow children to develop their social skills, negotiate rules, and practice taking on different roles within a community. Through these experiences, they are able to form their own moral code and develop their identity in relation to the group.

Children in this stage also have a thirst for knowledge that goes beyond what is available in the classroom. Montessori education encourages “Going Out” experiences—trips beyond the school to explore the wider world. These excursions allow children to engage with real-world problems, develop planning and execution skills, and build a deeper understanding of the subjects they are studying. Through these experiences, children come to see themselves as active participants in the world around them.

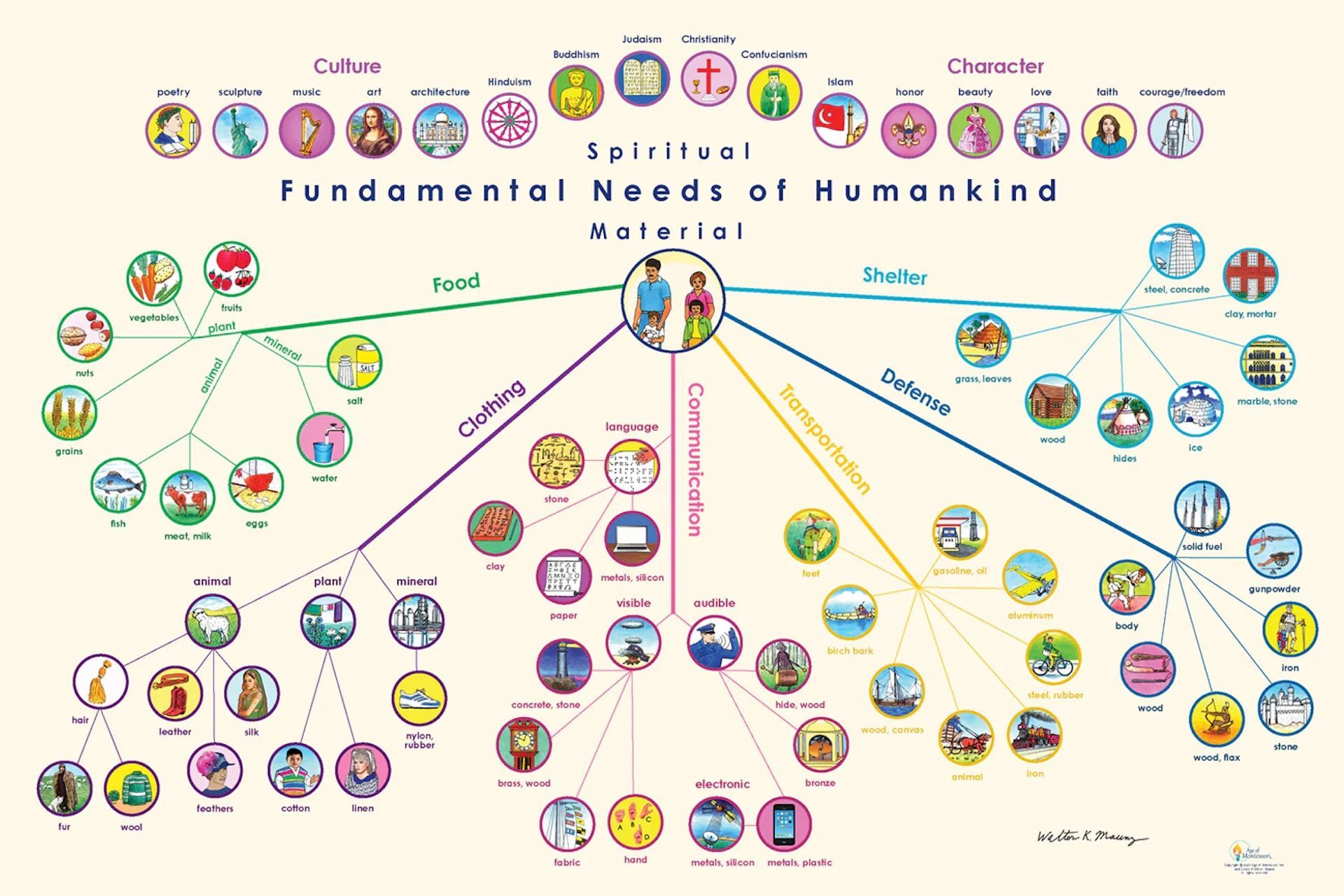

Montessori referred to the educational experience in the second plane as "cosmic education." In this phase, children are introduced to the universe as a whole, with an emphasis on the interconnectedness of all life. The Montessori curriculum for this stage revolves around the Five Great Lessons, which invite children into discovering more about the universe, the formation of the earth, the coming of plants and animals, the arrival of humans, and the development of written language and numbers. From these lessons, all areas of study—botany, geography, history, zoology, language, and more—emerge, inspiring awe and gratitude for the universe and humankind’s place within it.

Support from Home and Community

While second plane children are eager to explore beyond the family and classroom, they still require the strong support of their home, school, and peer group. Social activities become increasingly important, as group work provides them with the opportunity to practice collaboration, moral judgment, and self-expression. A strong, supportive environment—both at home and at school—helps children navigate this important stage in their development.

Curious to see how a school environment can meet the needs of six- to twelve-year-olds while inspiring deep learning? Schedule a tour of our classrooms!